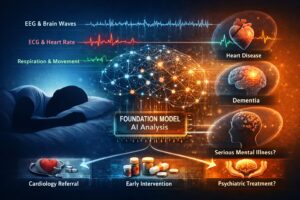

Stanford Researchers Build SleepFM Clinical: A Multimodal Sleep Foundation AI Model for 130+ Disease Prediction

Sleep is one of the few “tests” the human body runs every single night—quietly generating a dense stream of signals that reflect the brain, heart, lungs, muscles, and autonomic nervous system. Until recently, clinical sleep studies (polysomnography, or PSG) were used mainly for narrow goals like sleep staging and diagnosing sleep apnea. But a new line of research from Stanford Medicine argues that a single night of PSG contains far more predictive value than clinicians typically extract.

That’s the idea behind SleepFM Clinical: a multimodal sleep foundation model designed to learn general-purpose representations from PSG data and then transfer those representations to a wide range of downstream clinical tasks—most notably predicting future disease risk across 130+ conditions from one night’s sleep signals. The work is reported in Nature Medicine and is accompanied by open-source resources that make it easier for other researchers to reproduce and extend the approach.

This article breaks down what SleepFM Clinical is, why “multimodal sleep” matters, how the model is trained, what “130 disease prediction” really means, and where the approach could go next.

What is SleepFM Clinical?

SleepFM (and its clinical implementation often discussed as “SleepFM Clinical”) is a foundation model trained on multimodal polysomnography recordings. “Foundation model” here means a model trained broadly (often self-supervised or weakly supervised) to learn versatile representations that can be adapted to many tasks with relatively little extra labeled data.

In the SleepFM study, the model is trained on ~585,000 hours of PSG data from 65,000+ participants, using multiple physiological channels commonly collected in sleep labs (e.g., EEG, ECG, EMG, respiratory signals). The authors describe the architecture as channel-agnostic, meaning it’s designed to handle different PSG configurations across cohorts and clinics without falling apart when certain channels are missing or recorded differently.

Once trained, SleepFM can be evaluated on classic sleep tasks (sleep staging, sleep apnea severity) and—crucially—used to generate embeddings that serve as features for long-horizon outcome prediction (disease risk, mortality, etc.).

Why “multimodal” sleep data is a big deal

Most consumer sleep tracking focuses on a narrow slice of physiology—often movement and heart rate via wearables. PSG is different: it’s a high-resolution clinical recording that captures multiple systems at once. A typical PSG may include:

-

EEG (brain activity) for sleep staging and neural signatures

-

ECG (heart activity) for rhythm and autonomic patterns

-

EMG (muscle activity) for movement-related physiology

-

Respiratory signals (airflow, effort, oxygen saturation) for breathing irregularities

These streams interact. For example, disordered breathing can trigger arousals reflected in EEG, produce oxygen desaturation, change heart rate variability, and fragment sleep architecture—all in the same night. SleepFM’s bet is that letting a model learn from all of this jointly is the only way to capture “the language of sleep” at clinical depth.

The core research question: Can one night of sleep predict future disease?

The headline claim is bold: from one PSG night, the model can predict risk for 130 conditions (out of 1,000+ categories evaluated) with clinically meaningful accuracy.

To do this, the researchers link PSG data to long-term electronic health record (EHR) outcomes from a large Stanford clinical population—reported as ~35,000 patients treated between 1999 and 2024 for the disease-prediction analyses.

The paper reports performance using the concordance index (C-index), a standard metric for risk prediction / time-to-event models (a C-index of 0.5 is chance; higher is better). The PubMed summary highlights that SleepFM achieves C-index ≥ 0.75 for the predicted conditions and gives examples such as:

-

All-cause mortality (C-index ~0.84)

-

Dementia (~0.85)

-

Myocardial infarction (~0.81)

-

Heart failure (~0.80)

-

Chronic kidney disease (~0.79)

-

Stroke (~0.78)

-

Atrial fibrillation (~0.78)

Some reporting around the study notes that for certain categories (including some cancers and other conditions), accuracy can exceed 80% in their analyses—though it’s important to interpret such statements in the context of the specific metric and task framing used.

How SleepFM Clinical works (conceptually)

Even without diving into code, you can understand SleepFM Clinical as a three-layer stack:

1) Pretraining on raw PSG to learn general representations

Instead of learning only to classify sleep stages, the model is trained to learn rich internal representations from large-scale multimodal sleep recordings. Because PSG captures multiple physiological systems, the representation can encode patterns of fragmentation, arousals, cardio-respiratory coupling, autonomic instability, and more—often beyond what’s captured by handcrafted clinical summary metrics.

2) Validating on standard sleep tasks

Before claiming long-term disease prediction, the study evaluates SleepFM on sleep staging and sleep apnea severity—tasks where clinicians already have established baselines and where models can be compared. Reuters’ summary notes SleepFM performed as well as or better than existing state-of-the-art models in these standard tasks.

3) Disease prediction via embeddings + time-to-event modeling

The disease prediction step is typically not “end-to-end deep learning that outputs 130 diagnoses.” Instead, SleepFM generates patient embeddings, and the researchers fit survival-style models (e.g., Cox models) on top of those embeddings for each disease grouping (often mapped from diagnosis codes to standardized groupings). This approach makes the prediction problem more interpretable and statistically grounded for time-to-diagnosis outcomes.

What “130+ disease prediction” actually means

This is the part that headlines can oversimplify. The model is not saying: “you will get disease X.” It’s closer to:

“Based on the physiological patterns in this PSG, your risk ranking for certain future diagnoses is higher/lower compared to others in the dataset, and the model can do this reliably enough (by C-index thresholds) for 130 categories.”

A few nuances matter:

-

It’s risk prediction, not a diagnosis. The outputs are predictive signals that could guide screening or follow-up—not a clinical determination on their own.

-

It’s anchored to a clinical population. These are people referred for sleep evaluation, not a random sample of the general population—so prevalence and risk profiles differ.

-

It’s limited to conditions where sleep carries detectable early signatures. The model screened 1,000+ categories and found a subset with strong signal. That’s a feature, not a bug: it suggests sleep is informative for many—but not all—disease pathways.

Why sleep might contain “early warnings” for so many diseases

From a physiological standpoint, sleep is a stress test in reverse: the body cycles through distinct states, and small instabilities become easier to detect:

-

Neurodegeneration and cognition: Sleep architecture changes, REM/NREM patterns shift, arousal thresholds change, and autonomic regulation can drift—sometimes years before overt symptoms.

-

Cardiovascular disease: Heart rate variability, nocturnal arrhythmias, breathing-related stress, and oxygen saturation dynamics can reflect latent risk.

-

Metabolic and kidney disease: Autonomic balance, sleep fragmentation, and respiratory instability can correlate with systemic health and inflammation.

-

Cancer and chronic illness: Sleep disruption can be both cause and consequence; it may reflect underlying physiologic strain, medication effects, or early disease burden.

The Stanford/Reuters reporting emphasizes that the model finds hidden patterns across the brain, heart, and breathing signals that clinicians may not routinely quantify today.

What makes SleepFM Clinical “clinical,” not just academic

A lot of AI models perform well in a single dataset and fail elsewhere. SleepFM’s “clinical” value comes from design choices aimed at real-world variability:

-

Channel-agnostic architecture: Sleep labs don’t always collect identical channels or sampling rates; a model that assumes a fixed set breaks easily. SleepFM is described as accommodating varying PSG configurations across cohorts.

-

Large-scale pretraining: 585,000 hours is not “small medical AI.” It’s foundation-model scale for PSG, which helps generalization.

-

Open-source implementation: The existence of a public repository lowers the barrier for evaluation by external groups—critical for clinical credibility.

Potential real-world applications

If findings like these hold up across external validation, SleepFM Clinical could reshape how sleep studies are used.

1) Turning PSG into a multi-disease risk screen

Many patients already undergo PSG for sleep apnea or unexplained fatigue. If the same test can also flag elevated risk for dementia, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, or stroke, it could help clinicians prioritize follow-up and prevention.

2) Better triage and personalized sleep medicine

Instead of treating “apnea severity” or “sleep fragmentation” as the sole outputs, a foundation model can produce a richer patient fingerprint that helps tailor treatment: CPAP adherence strategies, cardiology referrals, neurocognitive screening, etc.

3) Accelerating research into sleep–disease mechanisms

SleepFM embeddings could act as a compressed representation of sleep physiology that researchers can correlate with genetics, labs, imaging, and outcomes—potentially revealing new phenotypes.

Key limitations and what to watch next

This research is promising, but clinical deployment requires caution. Here are the big questions the community will likely push on:

-

External validation across hospitals and geographies: A model trained largely on one center’s clinical PSG + EHR linkage can inherit local biases (referral patterns, coding practices, devices).

-

Fairness and subgroup performance: Does prediction work equally well across age groups, sexes, and underrepresented populations?

-

Clinical actionability: If the model flags elevated risk, what is the recommended next step—and does that step improve outcomes?

-

Data drift and changing clinical practice: PSG hardware, scoring guidelines, and EHR coding evolve over time—models must be monitored.

-

Interpretability: Clinicians will want to know which patterns drive risk predictions and whether they match known physiology.

The Nature Medicine publication establishes scientific credibility, but translation will depend on replication, prospective studies, and clear clinical pathways.

Ethical and privacy considerations

Any model that links biometric signals to long-term health outcomes raises serious issues:

-

Privacy of raw physiological data: PSG is deeply identifying; governance and security must be strong.

-

Risk of overdiagnosis or anxiety: A risk score can cause harm if presented without context or follow-up options.

-

Clinical responsibility: Who “owns” the result—sleep clinics, primary care, specialists—and how is it documented?

-

Regulatory oversight: A system used for clinical decision support may require formal evaluation and approval processes.

These concerns aren’t unique to SleepFM, but the breadth of “130 conditions” amplifies the importance of safeguards.

The bigger trend: Foundation models move into clinical time-series

SleepFM Clinical sits inside a broader shift: foundation models are expanding from text and images into clinical time-series (ECG, EEG, vitals, waveforms). Sleep is uniquely suited because PSG is rich and standardized enough to support pretraining at scale—yet underutilized in routine care.

If future work shows reliable generalization, you can imagine a world where:

-

PSG is used not only to diagnose sleep disorders, but also to assess systemic risk,

-

sleep lab reports include representation-based biomarkers (not just AHI),

-

and “sleep age” or “sleep phenotype” becomes a clinical construct tied to prevention.

Conclusion

SleepFM Clinical is an ambitious attempt to treat sleep as a high-information, multimodal window into long-term health. By training a foundation model on ~585,000 hours of PSG from 65,000+ people and linking sleep embeddings to longitudinal EHR outcomes, Stanford researchers report the ability to predict risk for 130 conditions—including major outcomes like dementia, heart attack, stroke, kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and mortality—based on a single night of sleep.

The most exciting implication isn’t just “AI predicts diseases.” It’s the reframing of PSG: from a narrow diagnostic procedure into a potential general health signal—one that could support earlier intervention, better triage, and deeper scientific understanding of how sleep and disease intertwine.

As always with medical AI, the next chapter is the hardest: external validation, subgroup fairness, clinical integration, and proof that acting on these predictions actually improves patient outcomes. But the foundation has been laid—quite literally.

For quick updates, follow our whatsapp –https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VbAabEC11ulGy0ZwRi3j

https://bitsofall.com/agentic-ai-langgraph-openai/

https://bitsofall.com/implement-softmax-from-scratch/

OpenAI “Atlas” AI Browser: The Next Evolution of Web Browsing (and Why It Matters)